How to Grow and Care for Ironweed (Vernonia)

An adaptable flowering perennial, ironweed is easy to grow in tough soils and is beloved by pollinators. Learn how to grow Vernonia now on Gardener’s Path.

Vernonia spp.

A true titan among wildflowers, the often imposing, hardy, and reliable ironweeds are typically tall, easy to grow, and an absolute favorite among pollinators.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Capable of flourishing in some truly tough spots, these flowers take care of themselves and put on a wonderful display when the garden’s riot of summer color is waning.

Read on to find out more about growing this late summer show-stopper.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

- What Is Ironweed?

- Cultivation and History

- Propagation

- How to Grow

- Growing Tips

- Pruning and Maintenance

- Species and Cultivars to Select

- Managing Pests and Disease

- Best Uses

- Quick Reference Growing Guide

What Is Ironweed?

A member of one of the largest flowering plant families on earth, Asteraceae, ironweed belongs to the genus Vernonia, named for the English botanist William Vernon.

Although the exact number of species is debatable, the genus is widely distributed around the globe and appreciated in horticulture for the fortitude that gave the plants their common name.

This large group of perennials occupies a variety of habitats including open woodlands, to montane cloud forests, to roadside ditches, wet riparian areas, and old fields.

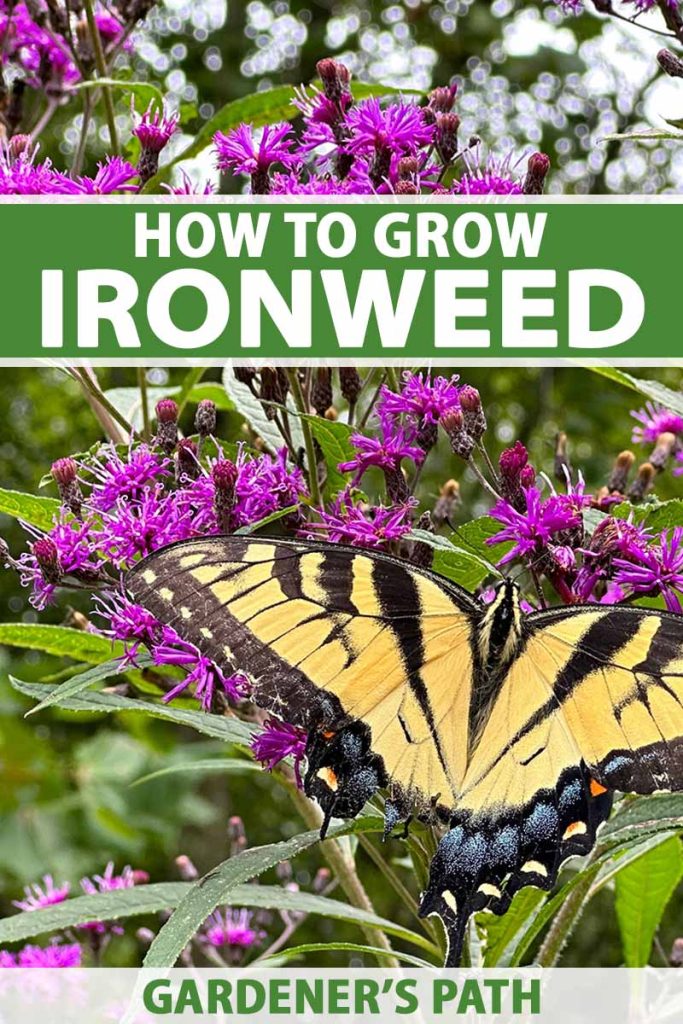

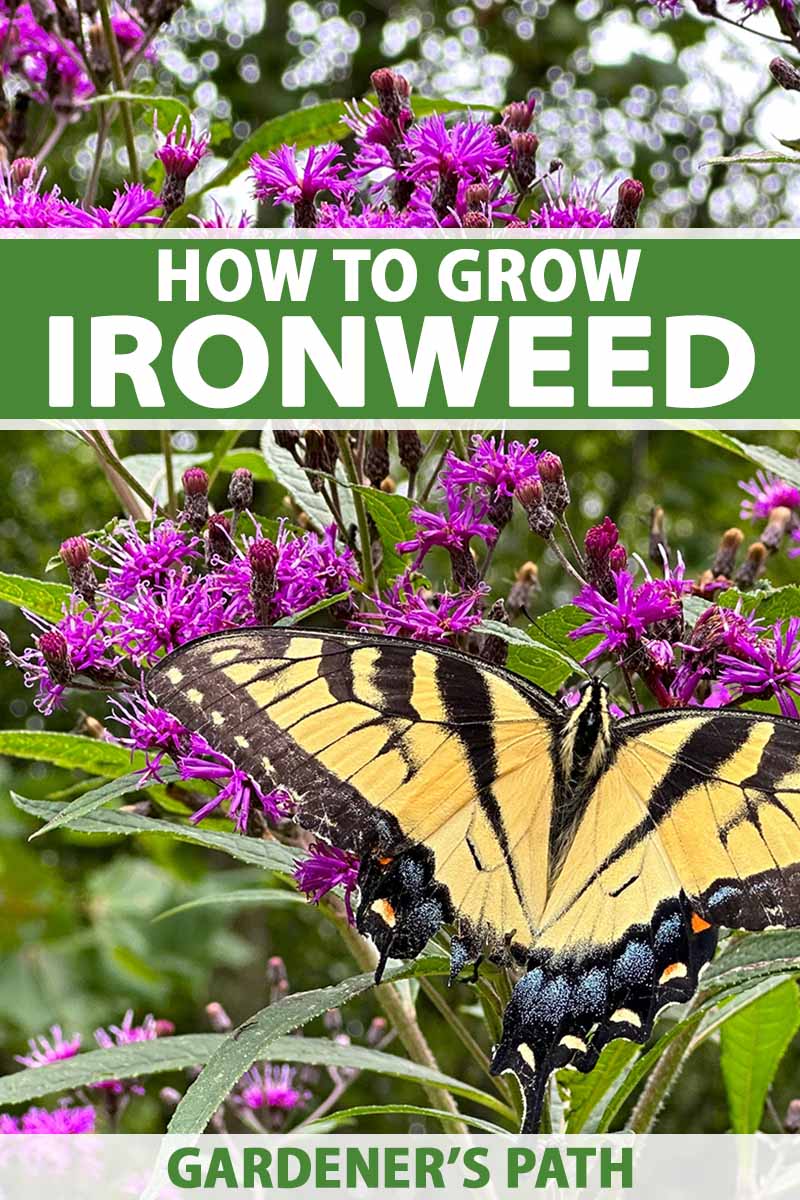

There is a lot of diversity within the genus, but all species produce bright purple to pink flowers composed of what are known as disk flowers.

Disk flowers are small, tubular, fertile flowers tightly packed together to form what’s known as an inflorescence. In ironweed, this aggregation of disk flowers look like beautiful, purple pom-poms that emerge in summer to early fall.

Ironweed leaves are typically toothed and are arranged alternately on the stem. Many species have a potent mixture of unpalatable chemicals that render them resistant to nibbling from deer, rabbits, and other herbivores!

The approximately 22 Vernonia species native to North America generally appreciate sunny conditions in reasonably moist, loamy soils. These species are all herbaceous.

Further afield, in tropical Africa, some members of this genus are shrubs, such as the important medicinal plant V. amygdalina, and capable of tolerating extremely arid conditions. The diversity in this large group of plants is vast.

In horticulture, the most popular ironweed varieties are derived from North American species, such as V. arkansana, V. gigantea, V. lettermannii, and V. noveboracensis.

Although these plants are remarkably easy to grow, their enormous size can sometimes be a little off-putting to gardeners, especially those short on space.

The species V. gigantea, for example, can grow to more than eight feet high. Fortunately, plant breeders have created more compact options for gardeners not ready to branch out, including the diminutive ‘Iron Butterfly,’ a V. lettermannii cultivar, which reaches two to three feet tall.

All ironweed cultivars on the market sport the same vibrant flowers. More on that later.

Adding this plant’s striking purple flowers to your garden’s palette isn’t the only gift ironweed has to offer.

This tenacious perennial is the perfect plant for North American wildlife gardens, too.

Ironweed flowers are excellent nectar sources for pollinators, providing food just as many types of butterflies are beginning to migrate in the fall. The seed heads are good food for birds that choose to stick around through winter, too.

Cultivation and History

Humans and ironweed have long enjoyed a close relationship. Before we were planting gardens for aesthetic reasons, the species in this genus were popular for remedying a whole host of physical ailments.

The cocktail of alkaloids and flavonoids that make ironweed’s bitter leaves so off putting to bunnies and deer also endow the plant with its purported anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory qualities.

An infusion of ironweed roots was used by the Cherokee to treat a number of different ailments including toothache, stomach ache, and hemorrhage.

The kiowa used V. missurica as a cure for dandruff, and were known to chew the perennial’s purple flowers, simply for their sweet taste.

Applications for this large and diverse genus abound. Today, some species, including V. cinerea, are being investigated for their use as oil crops, and others, such as V. galamensis, as anti-inflammatories for relieving arthritis.

Ironweed Propagation

To grow ironweed in your own garden you’ll need plenty of space.

Most North American species in the Vernonia genus form tall, dense clumps that can shade out neighboring plants. Make sure you leave one to four feet between plants, depending on the species you choose to grow.

Beyond that, the ironweeds are a pretty unfussy bunch and can thrive in lean to rich soils, wet to dry conditions, and even tolerate a little afternoon shade.

Generally speaking, you can grow ironweed from seed, via cuttings, by division, or from purchased nursery starts. Read on to find out the ins and outs of each method.

From Seed

The most cost-effective way to get this leggy native established in your garden is to purchase – or better yet, collect from the wild – a handful of ironweed seeds.

If you want to collect seed from wild plants, identify a population in late summer, when the bright purple flowers are easiest to see.

Collect the seed once the flowers have fluffed out and produced a white “pappus” – the fluffy parachute-like appendage that helps a seed fly. Usually this happens around October.

Store the seeds in a paper envelope out of direct sunlight until you’re ready to sow. The sooner you sow your seeds, the better their chance at germinating.

You’ll have the most success germinating seed if you emulate mother nature’s process: in fall, sow seeds on the surface of the soil in a prepared spot in the garden with adequate space to grow these typically large plants.

Push the seed firmly into lightly raked soil and barely cover. A handful of dirt sprinkled over the top will suffice, as these seeds need a little light to germinate. The cold winter weather will stratify the seed and prepare it for germination come spring.

Make sure the seeding area stays free from weeds, and, once spring arrives, water liberally in the absence of rain, making sure not to disturb the soil and any new seedlings that might already be emerging.

Once your baby ironweeds reach a few inches in height, you can carefully transplant them to other areas of the garden if you want to move them somewhere else. Make sure to disturb their roots as little as possible when digging them up.

Ironweed seed can be started indoors, too, but the germination rates can be very patchy, and I don’t recommend this method. Before sowing, the seed must be cold stratified for 30 to 60 days in the fridge in a zip-lock bag with moist perlite.

If you don’t want to direct-sow, I’d recommend sowing your seed in plastic flats, and placing them in a sheltered spot outside so the winter weather can do the job of stratification for you.

A back porch or up against the wall of your house is a perfect spot to keep them. Keep the soil moist, but not soaking wet.

Seedlings will emerge in spring and should be kept moist with regular watering. When your young seedlings are a few inches tall, transplant the most robust ones into a prepared location in the garden.

From Cuttings

Like many herbaceous plants, ironweed can be propagated via cuttings taken from the new growing tips of the plant’s stems.

Fill several four-inch pots with moist perlite. Prepare enough pots to accommodate one cutting per pot.

Take a cutting of pliable, soft growth in late spring, making sure each piece is about six inches long.

Remove the leaves from the bottom half of the cutting and dip each cut end in rooting hormone. Bury the bottom two inches of the cutting in your prepared pots and water in well.

Tent the cuttings with a plastic bag and place them in a location indoors that receives plenty of indirect sun, but where they won’t roast. The greenhouse effect of the plastic bag over the cuttings can amplify sunlight, actually burning your tender cutting’s leaves.

The plastic tent should work to keep internal conditions stable but check the surface of the soil every day to make sure it’s moist. If it isn’t, water, and securely seal the bag around your pot.

After about six weeks, your ironweed cuttings should begin to root. Give each plant a couple of extra weeks to establish a strong root system and then transplant out in the garden, as discussed below.

Via Division

If you’re lucky enough to have a friend or neighbor that grows ironweed, see if you can scoop up a division from them in the fall or spring. Divisions are essentially a slice of a mature plant’s root system.

The best times to divide are in spring when little leaves have just begun to emerge, or in the fall, once the plant has finished producing seed and has died back considerably.

Using a sharp, flat edged spade, cut the root mass completely in half, down the center. Gently work around the outside of the portion of the plant you want to remove, prying it up from the ground. Backfill the hole and water the remaining in-ground plant well to prevent stress.

Transplant to your desired location as discussed below.

Transplanting

The easiest way to establish ironweed is by purchasing a potted plant from a nursery.

Site your new addition in an area of the garden with an appropriate amount of space for the expected mature dimensions of the species you have chosen. If it’s one of the larger types, it may need as much as three to four feet of space around it.

Choose a location with full sun and rich soil that isn’t too dry.

Dig a hole the same depth and slightly wider than the width of the current container the plant is growing in. Or, in the case of a division, as deep as the root system.

Gently remove the plant from its container, set it in the hole, and backfill with soil so it sits at the same depth as it was in the original container. Water in well.

How to Grow Ironweed

Ironweed is a low maintenance choice and is hardy in Zones 4 to 9. However, just like any other plant, while it’s young it will require a little extra love and care.

Remove weeds around the plant so they don’t compete for water and nutrients and make sure the soil remains consistently moist while transplants are becoming established.

Site plants in soil with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0, and, if possible, in full sun.

These wildflowers can thrive in almost any type of soil but prefer moderately rich loams.

For ironweeds growing in nutrient-poor soils, top dress your plants in the spring and fall with three or more inches of compost and water well so nutrients trickle down to the roots.

Although species in the Vernonia genus can tolerate drought conditions for short periods, if grown in consistently dry conditions, they will need regular watering in the absence of rain. Generally, a once-a-week deep watering should be sufficient.

Roadside ditches, and low wet spots in open meadows are favorite spots for this native flower in the wild.

True to its common name, ironweed can withstand hardpan, dried out soil or sopping wet feet. For this reason, it’s an ideal plant for a rain garden that experiences variable and intermittent moisture.

Maybe you have somewhere like that at home? A long-forgotten soggy spot that dries out in summer? The edge of an ephemeral marsh?

Or maybe you just want to enjoy ironweed at the back of your flower border and water well during dry spells. This native is incredibly tough and will find a way to flourish almost anywhere. Just remember to give it plenty of space to spread out!

Growing Tips

- Plant in average to rich, moist to dry soils.

- Provide plenty of space, at least three feet for taller species, so mature plants can spread.

- Site in a location with full sun.

- Water well during prolonged dry periods.

- Top dress with compost in spring if growing in poor soil.

Pruning and Maintenance

Ironweed is such a tough cookie, it can be left virtually to its own devices.

Truly, what’s more lovable than that? Some gardeners may choose to cut down browned stems and dead flower heads, but those old hollow stems actually provide important overwintering homes for bees and other insects if left standing.

You can remove old stems in late spring once the weather warms, or better yet, just let them degrade naturally in the garden, providing even more beneficial habitat and organic material for the soil.

Ironweed will self-seed, so if you don’t have room for more than one of these larger than life wildflowers, prune off spent flower heads in fall, or just remove any seedlings that pop up in spring.

Spring and fall are the perfect times to divide mature plants, too.

Ironweed Species and Cultivars to Select

As mentioned before, the species widely available to home gardeners are North American in origin, though they vary in size and have some slight differences in habitat preferences.

Luckily for us, however, they’re all equally tough and produce the same deep purple blooms come summer’s end.

One further word to the wise: be careful when selecting cultivars to stay away from those described as pollenless. These traits can escape into wild populations and affect the pollinators that depend on these wild plants for food.

Arkansana

V. arkansana (syn. V. crinita), or great ironweed, is typically found growing along rivers, and in wet sloughs but it can also tolerate dry soils.

Growing up to five feet tall and four feet wide, this species offers a compact option for the garden. V. arkansana is hardy in USDA Zones 5 to 8.

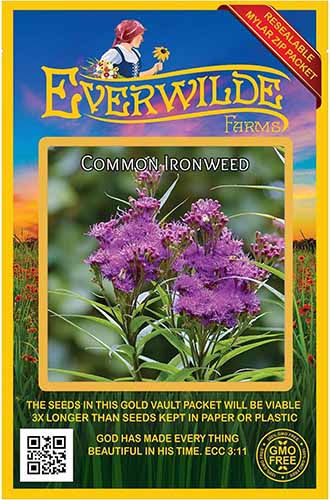

Fasciculata

V. fasciculata, aka common or prairie ironweed, is hardy in Zones 4 to 9, and reaches a mature height and spread of two to six feet.

It features violet-purple flowers borne atop sturdy stems.

Vernonia fasciculata

You can find seeds available in packets of 500 from Everwilde Farms via Walmart.

Gigantea

V. gigantea (syn. V. altissima), also known as giant ironweed, has flowers in varied hues of lavender, magenta, and deep purple.

The truly unique aspect of this species, however, is its gargantuan size. When grown under optimal conditions, V. gigantea can reach 10 feet tall.

This species is hardy in Zones 5 to 9 and is moderately resistant to powdery mildew.

‘Jonesboro Giant’ is one of the largest cultivars on the market, reaching a mature height of almost 12 feet tall, with rigid, upright stems.

Lettermannii

The diminutive V. lettermannii, or narrowleaf ironweed, tops out at around two to three feet tall. Its needle-shaped, fine leaves add a beautiful, soft texture to the garden in Zones 4 to 9.

‘Iron Butterfly’ is a cultivar that looks very similar to the species plant, but is a little more compact, reaching just two feet tall.

‘Iron Butterfly’

It is exceptionally robust and highly resistant to powdery mildew.

You can find ‘Iron Butterfly’ available in #3 containers from Nature Hills Nursery.

Noveboracensis

Another species popular in horticulture, V. noveboracensis, or New York ironweed, prefers slightly acidic, rich moist soils and is a little more compact than giant ironweed, topping out at around eight feet tall.

This species is hardy in Zones 5 to 9.

Summer’s Surrender

‘Summer’s Surrender’ is a hybrid of V. lettermannii and V. arkansana. This cultivar is dense and broad reaching about six feet across once mature.

Growing to heights of approximately four feet, this showy cultivar is densely covered in blossoms beginning in September.

‘Summer’s Surrender’ is hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 9.

Summer’s Swan Song

‘Summer’s Swan Song’ is a hybrid cross of V. lettermannii and V. angustifolia, and is another compact choice for the gardener with little space. This cultivar grows to about three feet high with a similar width.

Highly resistant to disease, ‘Summer’s Swan Song’ produces deep purple flowers from early September to early October.

This cultivar thrives in USDA Zones 4 to 9.

Managing Pests and Disease

Like many other native species, Vernonia is plagued by very few diseases, and even fewer pests.

This is truly a plant for the armchair gardener.

Herbivores

Ironweed’s leaves are endowed with a suite of bitter compounds which make them unpalatable to all but the most desperate of herbivores.

If you notice any nibbling, it will undoubtedly be due to the host of insects that depend on these species for food.

Insects

While plenty of insects rely on ironweed, from the wide-ranging painted lady butterfly to the parthenice tiger moth, few bugs, if any, do damage that need concern a gardener.

Disease

Thankfully, ironweed is as tough as the name suggests. There are really only a couple diseases that afflict these resilient plants.

Powdery Mildew

This easily-recognizable disease typically appears during dry spells, when plants are stressed.

Caused by a number of different species of fungi, this affliction is especially common in densely-planted areas with poor air circulation or low light, it appears initially as white spots on young leaves.

If you’re lucky enough to catch the fungal infection just as it’s starting to take hold, pull off any affected leaves and destroy them by burning or tossing in the garbage – don’t place them on the compost pile as composting won’t destroy the fungal spores.

If your plants are in the shade, or somewhere where the soil is too dry, consider moving them to better conditions.

Remember, optimal conditions for ironweed are full sun and moderately moist soils. Watering more diligently can also help avoid the drought stress that may allow powdery mildew to get a foothold, too.

Also, be sure to always water at the soil level, not on the leaves. Wet foliage can cause powdery mildew to spread.

In healthy plants, powdery mildew shouldn’t affect flower or seed production too much.

If you’re concerned, spraying neem oil or another fungicide can be effective and help to prevent another outbreak, but it’s not really necessary.

Learn more about powdery mildew and how to deal with it in our guide.

Rust

Although rust is not a common problem in ironweed, the bumpy, orange-colored blemishes this disease creates can be a nuisance.

The condition itself can be caused by a huge number of different fungi, but fortunately, rust is usually self-limiting and resolves with pruning of affected foliage and a good clean up of any potentially diseased leaf litter.

Plants typically become susceptible to rust if they’re growing in overcrowded, warm, humid conditions. Providing adequate spacing between plants and watering at ground level, rather than overhead, can do a lot to keep your plants rust-free.

If you want to apply a fungicide and are comfortable doing so, you can use neem oil.

Bonide Neem Oil

You can find Bonide Captain Jack’s available at Gardener’s Supply Company in 32-ounce ready-to-spray bottles.

However, neem oil is toxic to bees, and I’d only recommend using it if the disease is severe.

If you go the fungicide route, make sure to wear gloves and follow all directions carefully.

Best Uses for Ironweed

Without a doubt, ironweed is best used in the native plant or wildlife garden, where it can attract flocks of granivorous birds, drifts of colorful butterflies, and swirls of every other kind of hungry pollinator.

Many species of caterpillar feed on the foliage of this important genus and its tall, woody stems provide important habitat for little critters through the winter months.

Try growing it in a spot that’s proven challenging for other species, where moisture levels fluctuate. Make a rain garden in an intermittently flooded spot and let it take over.

Some species, such as New York ironweed, have particularly showy purple flowers and these look wonderful and last quite a long time in cut flower bouquets, too.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous flowering perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | Purple to dark pink/deep green |

| Native to: | Africa, North America, South America, Southeast Asia | Tolerance: | Drought, deer, diseases, poor soil |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-9 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Bloom Time: | Late summer to early fall | Soil Type: | Organically-rich, moist loam |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part afternoon shade | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 2 years | Soil Drainage: | Moderate to moist |

| Spacing: | 2-4 feet or more | Attracts: | Bees, beetles, birds, butterflies, hummingbirds, wasps |

| Planting Depth: | Surface of the soil (seeds), or root ball even with the ground (transplants) | Uses: | Garden bed, naturalized areas, wildlife garden, rain garden, cut flower. |

| Height: | 2-12 feet, depending on species | Order: | Asterales |

| Spread: | 2-5 feet, depending on species | Family: | Asteraceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Vernonia |

| Common Diseases: | Powdery mildew, rust | Species: | Altissima, arkansana, gigantea, lettermannii, missurica, noveboracensis |

Nothing Tougher than Ironweed

Superstar of the eco-friendly yard, this pollinator magnet will be the belle of the late summer ball.

Tall, striking, and forever forgiving of a variety of tough conditions, give one of the ironweeds a try in your garden. I’m certain you won’t regret it.

Do you grow ironweed in your backyard? Which species? Tell us how it’s doing, where it’s growing, and what wonderful wildlife it attracts. Comments are always welcome!

To learn more about ironweed’s equally laid back, tough-as-nails wildflower relatives, check out the following guides next:

- How to Grow and Care for Spotted Joe-Pye Weed

- How to Plant and Grow Bee Balm

- How to Grow and Care for Rosinweed