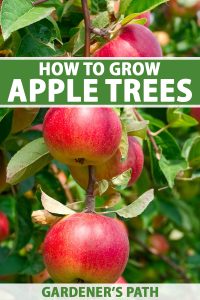

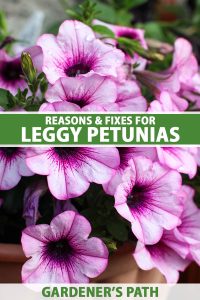

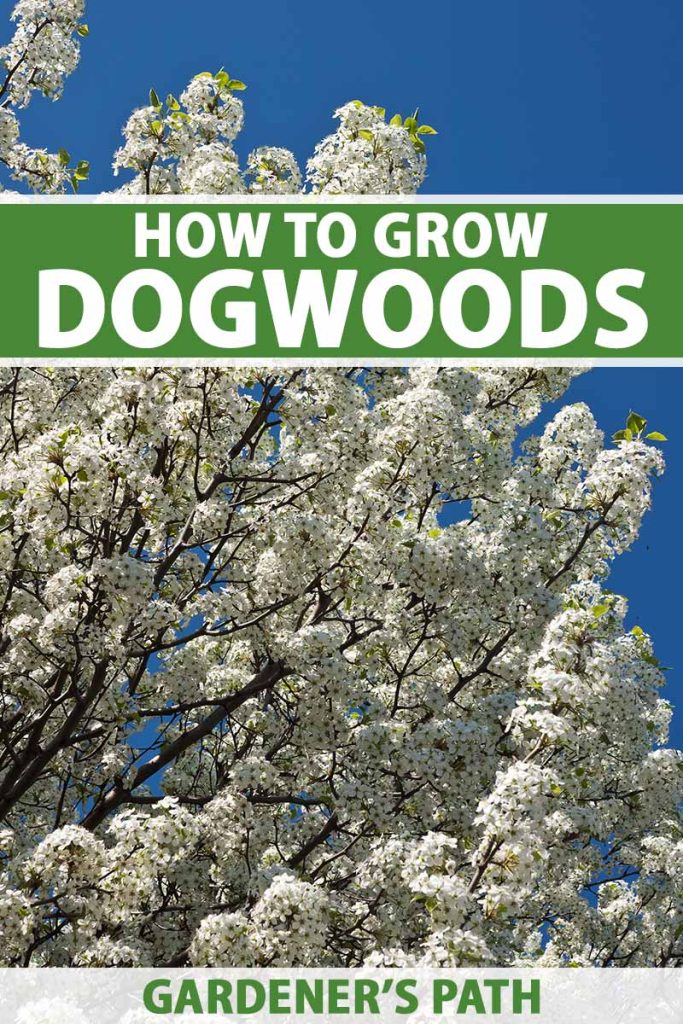

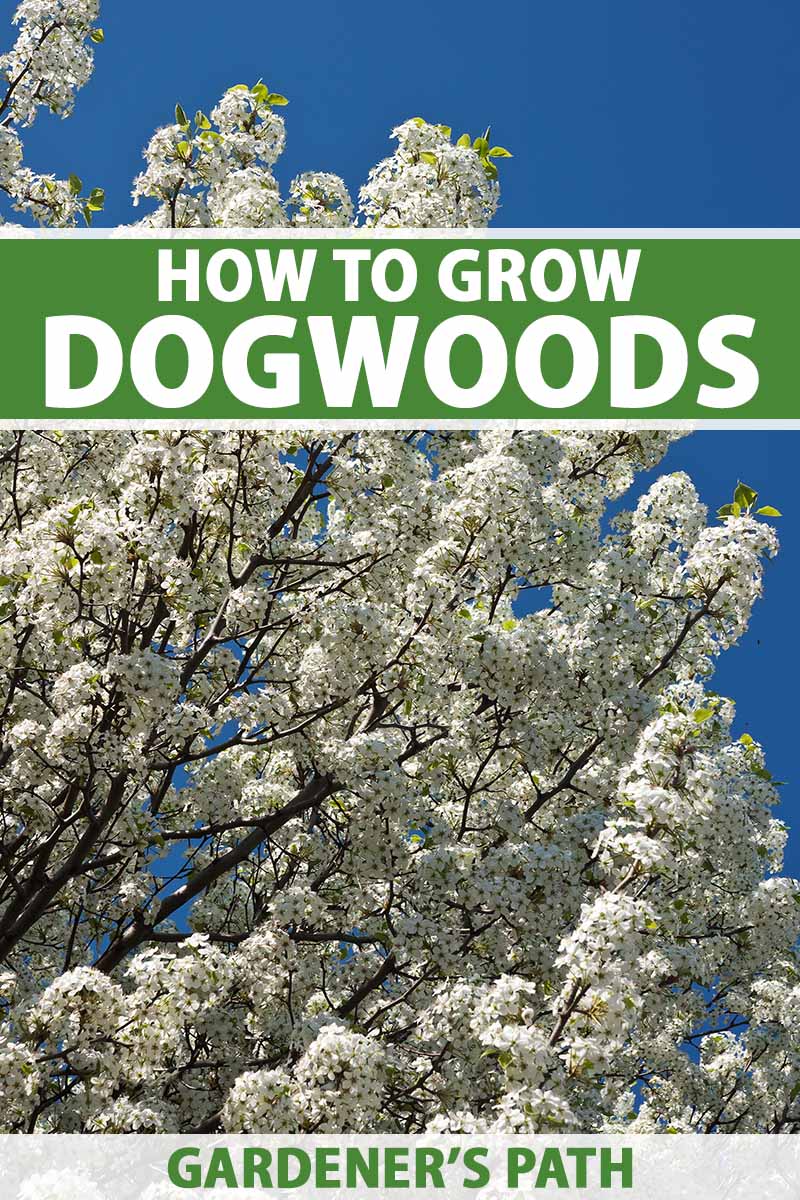

How to Grow and Care for Dogwoods

Dogwoods may be trees, shrubs, or ground covers, and all are gorgeous additions to the landscape. Learn how to grow Cornus species on Gardener's Path.

Cornus spp.

Looking for beautiful, fascinating plants that amaze, astound, and astonish? Sounds like you’re in need of a dogwood or two.

It’s rare for plants to have attractive leaves, bark, flowers, fruits, and forms. For most plants, usually at least one of those qualities is considered aesthetically meh, if not bleh.

Not dogwoods, though – those have a rating of five stars pretty much across the board.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

And even though they’re metaphorically and literally overshadowed by larger trees, understory species like dogwoods have their merits. For a gardener looking to pepper their landscape with pretty ornamentals that don’t dwarf their home, Cornus species have a lot to offer.

So strap yourself in, dear reader. We’ll be discussing how to cultivate these lovely plants and how to best use them in your landscape. We’ll also cover a handful of our favorite species.

Here’s what we’ll be getting into:

What You’ll Learn

- What Are Dogwoods?

- Cultivation and History

- Propagation

- How to Grow

- Growing Tips

- Pruning and Maintenance

- Species to Select

- Managing Pests and Disease

- Best Uses

- Quick Reference Growing Guide

What Are Dogwoods?

Containing 57 currently recognized species of trees, shrubs, subshrubs, and even perennial ground covers, the Cornus genus is part of the Cornaceae family along with its sister genus Alangium.

Collectively hardy in USDA Zones 2 to 10, species of Cornus are distributed across the Northern Hemisphere in Asia, Europe, and North America.

In the United States, you can pretty much find a species of dogwood in any region of the country, save for the hottest and driest of climates.

Taxonomists have identified four clades within the genus: blue- or white-fruited types, big-bract types, dwarf types, and cornelian cherries, though these descriptions are seldom used by gardeners or horticulturalists.

The name Cornus comes from the Latin word cornu, meaning “hard” – a reference to the super dense and fine-grained wood of dogwood species.

Speaking of common Cornus characteristics, let’s go over what dogwoods generally look like.

Most species have simple, ovate, deciduous, and oppositely arranged leaves with parallel, arching leaf veins. A rich green or variegated during the growing season, these leaves tend to turn a deep burgundy red in fall.

Anytime from late winter to early summer, Cornus species bloom with flowers that have structures in fours: four lobes, four petals, and four stamens.

The flowers themselves aren’t all that showy, but they are encased in the middle of four to six petal-like leaf bracts that may be red, green, gold, yellow, pink, and/or white, depending on the species or cultivar.

When they’re in full bloom, dogwoods attract many pollinating insects, from bees to butterflies to moths. After pollination, the flowers give way to red, bluish-black, or white drupes, which attract hungry birds and mammals.

Along with spreading via seed dispersal, dogwood species can expand via underground rhizomes or even by rooting the tips of lower branches.

Dogwoods come in many different sizes, depending on the species.

Some, like the ground cover C. canadensis, top out at just four inches tall and spread pretty much indefinitely.

Others, like the red-stemmed C. sericea or its yellow-stemmed cultivars, are your moderately-sized, stereotypical shrubs. Other tree-like species can reach heights of 45 feet and spreads of 40 feet in cultivation!

Cultivation and History

Dogwoods have a rich history of cultivation, and the origin of the distinctly unique and interesting name can’t be said with a slam-dunk surety.

The name “dogwood” is thought to come from a colonial description of flowering dogwood fruits being edible, yet the taste not being fit for a dog. The hard, tough wood was also used for constructing skewers – i.e. “dogs” – so that could be the explanation, too. Take your pick!

The wood has been used across many cultures for constructing weapons, tool handles, loom shuttles, golf club heads, jeweler’s boxes, butcher blocks, and many other items that need to be able to withstand strong hits and high forces without taking damage.

Not all Cornus fruits are recommended for human consumption, but among those that are, some are quite tasty!

The cornelian cherry (C. mas) in particular has found some fame as the tastiest of the dogwood fruits, and is used in delicious sweet treats to this day.

It was also used back in Ancient Greece and Rome to dye fezzes, treat dysentery, and relieve gastrointestinal stress – and has even been mentioned in the literature of Homer and Ovid!

Many other species have had a variety of applications throughout history.

Extracts from the leaves of the Pagoda dogwood (C. alternifolia) have been used in traditional Chinese medicine as an analgesic, a diuretic, and a tonic.

Native Americans used parts of the flowering dogwood to treat colic and fevers, and even to make red dye. During the American Civil War, the tree’s leaves came in handy for making tea and as a substitute for quinine in compound tinctures.

And of course, dogwoods are beloved in the world of ornamental landscaping… that’s probably why you’re here, after all.

Dogwood Propagation

Many dogwood species can be grown from seed or propagated from cuttings.

You can also purchase nursery starts and saplings to transplant into the garden. Let’s go over these techniques, in order of descending difficulty.

But just as a reminder, there are a large number of different dogwoods out there, so the following tips are kept intentionally general.

From Seed

First things first: you’ll need seeds. Those can be bought from a reputable vendor, acquired from a friend, or even gathered yourself.

To gather seeds, you’ll first need to harvest the fruits they grow in, when they’re ripe. To ensure ripeness, only gather the fruits once they’ve dropped to the ground.

When you’ve gathered the fruits, you’ll need to mash them up to extract the seeds. You can do this by hand, with a mortar and pestle, or you can even use a blender.

Remove the seeds from the mashed fruits, set them on a strainer, and rinse off the pulp with water. You can also put the seeds in water, which will separate the pulp naturally. This will also separate viable seeds from non-viable ones, as the good seeds will sink and the duds will float.

You can either sow your Cornus seeds outdoors immediately in fall, or cold-stratify them before sowing in spring. To stratify, partially fill a plastic baggie with a 50:50 mix of peat moss and perlite, stick the seeds in, moisten the media, and leave the baggie in the fridge until spring.

Come spring, place the seeds half an inch deep in a seed tray filled with a similar peat/perlite mix, moisten the media, and set the container next to a sunny indoor window. Provide even moisture, but don’t allow the soil to become waterlogged.

When the seeds germinate and grow into seedlings, thin them out and/or repot them as needed to give them enough room to develop, all the while keeping the soil moist.

After they reach a suitable size – about three to four inches in height – they’ll be big enough to move outdoors.

When the final frost date passes, you’ll need to harden off the seedlings before transplanting. To do this, take the containers outside for 30 to 60 minutes before bringing them back inside.

Each subsequent day, add an additional half to full hour of outdoor time until they can spend a full day outdoors. From here, you can transplant!

From Cuttings

Anytime during the summer months, take four- to six-inch cuttings of softwood to semi-hardwood shoot tissue, depending on the species you are propagating.

Take these cuttings from the distal – or terminal – ends of shoots, and make your cuts with a sharp and sterile blade.

Defoliate the bottom half of each cutting, and dip the cut ends in a bit of IBA rooting hormone to help with root formation.

If you don’t have any rooting hormone powder, you can find Bonide Bontone II available from Arbico Organics.

Bonide Bontone II Rooting Hormone

Prepare a three- to four-inch container filled with a 50:50 mix of peat and perlite for each cutting, then stick said cuttings in, two to three inches deep. Moisten the media and place the containers next to a sunny window indoors.

Keep the media moist as the cuttings take root. When the cuttings have rooted and grown a couple of new leaves, they will be ready to harden off like you would with seedlings before transplanting.

Via Transplanting

Before you transplant, ensure that your planting site has the proper exposure for your chosen species. Additionally, make sure that you’re transplanting into rich, loamy, and well-draining soil with a pH of 5.0 to 8.0.

Whether you’re transplanting a seedling, a rooted cutting, or a nursery start, ensure that your planting site provides enough room for the transplant to reach its mature height and spread without bumping into buildings, walkways, or other plants.

The best transplanting times are spring, after the last frost, and fall, a couple of weeks before your average first frost date.

Seedlings and rooted cuttings simply need a transplant hole that’s large enough to accomodate their root systems.

For container plants from the nursery, you’ll need to make the hole a bit wider than the containers they come in, so you have room to work.

Gently remove the plant from its container, and set it in the hole. Backfill with soil, and water in well.

Bare root specimens should be soaked in water for several hours before transplanting. Once it’s time, dig a hole, make a mound of soil at the bottom, and spread the roots out over it.

Alternate backfilling with watering until the hole is filled in, give it one final watering, and you’re done!

Adding a bit of organic matter like compost to the soil you backfill with can provide your soil with some extra fertility to get your transplants off to a good start.

For your baby transplants, really stay on top of watering until they become established in a year or two.

How to Grow Dogwoods

All the different dogwood species have a lot in common in terms of their growing needs. For catch-all Cornus cultivation, let’s go over what works.

Climate and Exposure Needs

If you’re anywhere in USDA Hardiness Zones 2 to 10, there’s a dogwood species for you – but not all Cornus species are suitable for all Zones.

In general, dogwoods thrive in full sun to partial shade, depending on the species, and some can tolerate full shade.

It’s all about finding that perfect balance between just enough sun to induce flowering, without scorching the leaves.

Soil Needs

Rich, well-draining loam with a pH of 5.0 to 8.0 should serve your specimens well as they grow and mature. You can conduct a soil test to check if the soil in your garden needs any specific amendments.

You may have to make some species-specific adjustments, but since dogwoods can generally handle most soils as long as they aren’t bone-dry or soggy, don’t sweat this too much.

Regular amendments of organic matter help keep soil rich, so work one to two inches of compost or well-rotted manure into your plants’ root zones every spring.

Water and Fertilizer Needs

Many Cornus species prefer a soil that’s kept moist, at least most of the time.

So be sure to water whenever the top few inches dry out, in the absence of rain, and definitely whenever you can’t reach moist soil with a soil knife.

Usually, supplemental fertilizer isn’t necessary if you keep on top of your humus amendments every spring. But if your soil is especially poor, you can apply a balanced 10-10-10 (NPK) fertilizer in spring.

Growing Tips

- Provide full sun to partial shade.

- Make annual amendments of humus in spring.

- If you keep with humus amendments, then supplemental fertilizer shouldn’t be necessary.

Pruning and Maintenance

Some species put out suckers at their base, which should be pruned ASAP to keep up appearances. You should also remove dead, diseased, or dying branches whenever you happen to notice them.

As for dedicated sessions of pruning that shape your plant’s form and increase airflow, those should be done in spring, just before bud break.

Depending on the type of dogwood, you may not shape the plant at all, but rather opt for the “au naturel” look.

Fallen leaves should be raked up after they drop, unless you’ve got a woodland garden going. And always maintain a two- to four-inch layer of mulch over the root zone – that’ll suppress weed growth, conserve moisture, protect the roots, and just look real purty.

In winter, you can cease your watering while the ground is frozen.

Dogwood Species to Select

With 57 Cornus species to consider, you’re spoilt for choice! Are you looking for a tree, a shrub, or maybe some ground cover?

You really can’t go wrong with a Cornus, and if you want to read more about the different types of dogwood, check out our guide to 23 of the best varieties.

Let’s go over some top-tier species:

Cornelian Cherry

Hardy in Zones 4 to 8, C. mas originates from west Asia, along with the central and southern regions of Europe.

Reaching heights of 15 to 25 feet and spreads of 12 to 18 feet, this tree bursts with yellow flowers in March, which later give way to red or yellow olive-shaped drupes.

Along with being super appetizing to birds and small mammals, these cornels are what make the cornelian cherry famous, as they are quite delicious to humans.

Cornelian Cherry

For a cornelian cherry tree of your own, check out FastGrowingTrees.com.

Learn more about how to grow cornelian cherries in our guide.

Creeping

The only ground cover on our list, C. canadensis doesn’t let its “vertically challenged” status detract from its aesthetics.

A native of east Asia, Greenland, and northern North America, the creeping dogwood is hardy in USDA Zones 2 to 6 – the colder, the better.

Reaching a height of three to nine inches, this plant has the potential to spread indefinitely via its creeping rhizomes, albeit very slowly.

Blooming in late spring to early summer, the clusters of true flowers are green and discreet, but they’re surrounded by four white flower bracts, which are quite showy. Later, the flowers give way to small, scarlet-red berries, which will delight the birds.

Flowering

Native to southeastern Canada and eastern parts of Mexico and the United States, C. florida reaches heights of 15 to 35 feet and spreads of 15 to 40 feet.

Hardy in Zones 5 to 9, this tree arguably boasts the best blooms of the bunch.

Emerging in mid-spring, the true flowers have a backdrop of four lovely white leaf bracts, each with a maroon notch at the tip. After pollination, the flowers are eventually replaced with clusters of glossy red drupes.

There are many flowering dogwood cultivars available with blooms in a variety of colors.

Flowering Dogwood

You can find flowering dogwood with white flowers in #1, #2, and #3 containers available from Nature Hills Nursery.

For more information about how to grow flowering dogwoods, read our guide.

Kousa

A lot of dogwoods deal with pests and disease on the regular. Not C. kousa, though – this east Asian native is resistant to many common Cornus concerns.

Hardy in Zones 5 to 8, the kousa dogwood reaches heights and spreads of 15 to 30 feet, and flaunts lovely white to pinkish flowers in late spring that, if pollinated, eventually yield fruits that look a lot like raspberries.

Kousa

You can find kousa dogwoods in a variety of sizes, from two- to seven-feet, available at FastGrowingTrees.com.

And be sure to give our C. kousa guide a read to learn more about growing this species!

Pacific

Hardy in Zones 7 to 9, C. nuttallii is essentially the flowering dogwood of the western United States and southern British Columbia.

Reaching heights of 15 to 40 feet and spreads of 10 to 25 feet, this tree has spring-blooming flowers with six white leaf bracts and fruits that look like a cross between those of C. florida and C. kousa.

If you’re jonesing for a flowering dogwood yet live in the western US, then C. nuttallii is the one for you.

Pagoda

Native to eastern North America and hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 7, C. alternifolia is notable thanks to its – you guessed it – alternately arranged foliage.

Growing 15 to 25 feet tall and 20 to 32 feet wide, pagoda dogwoods bloom in late spring with small, yellow, bractless flowers that eventually yield small blue-black clusters of drupes that grow on red stems.

Pagoda

You can find C. alternifolia available at Nature Hills Nursery.

Need some pagoda dogwood knowledge? Give our guide a gander.

Red Twig

What makes red twig dogwoods special? It’s right there in the name!

A North American native that’s hardy in USDA Zones 2 to 7, C. sericea, aka red osier dogwood, has bright red stems – an awesome hue for a leafless, snowy landscape!

In late spring, this shrub produces white, flat-topped flowers, which later give way to clusters of globose white berries.

Red Twig Dogwood

Growing six to nine feet tall and seven to 10 feet wide, this red twig dogwood is a compact beauty.

You can find plants available at Nature Hills Nursery.

There are other species also commonly known as red twig dogwoods and you can learn about all of them in our guide. (coming soon!)

Tatarian

Native to northern China, North Korea, and Siberia, C. alba is a team player – a mass or line of them looks better than one on its own.

Hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 7, the tatarian dogwood is pretty moderately-sized, with a mature height and spread of eight to 10 feet.

In late spring, these shrubs bloom with clusters of small, yellowish-white true flowers, which eventually yield beautiful clusters of spherical white drupes.

Additionally, the stems of this plant turn blood red for the winter, a lovely change from the red-streaked green of the growing season stems.

‘Elegantissima’ is a charming variegated cultivar, sporting light green and cream foliage that turns red in fall, before dropping to reveal the bright red stems.

‘Elegantissima’

You can find ‘Elegantissima’ available at Nature Hills Nursery.

Managing Pests and Disease

Pests and diseases can cause all sorts of issues, from purely aesthetic problems to debilitating sickness, and as a whole, dogwoods are pretty susceptible to a lot of them.

Consider this the Achilles heel that makes these otherwise perfect plants imperfect.

In general, there are a bunch of tips and tricks for keeping problems at bay. Two of the smartest things you can do are cultivating your dogwood properly and sanitizing your tools between pruning different specimens.

Thankfully, these trees are deer-resistant. But there are many other pests that can wreck a dogwood.

You’ve got your all-too-common aphids, scale, and mealybugs, as well as the dogwood-specific borers, club gall midges, and sawflies.

Mammal-wise, you may deal with hungry chipmunks, raccoons, and even black-bears – if they are common in your region!

You’ll have plenty of potential problems on the disease front, too. Powdery mildew, Discula anthracnose, and root rots are but a few of the diseases you may have to deal with.

You can learn more about dogwood diseases and how to treat them in our guide.

Best Uses for Dogwoods

Individually, species of dogwoods are more suitable for certain landscape situations than others. But when unified as the Cornus genus, there’s not much they can’t do.

If you need a plant for establishing a border, placing along a home foundation, grouping in a cluster, adding to a native garden, attracting wildlife, growing under a canopy as an understory planting, or displaying as a specimen… don’t worry. There’s a dogwood for the job.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Landscape trees, woody shrubs and subshrubs, perennial creeping ground covers | Flower/Foliage Color: | Green, gold, pink, red, white, yellow/green, variegated |

| Native to: | Asia, Europe, North America | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 2-10, depending on species | Tolerance: | Deer, full shade |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Late winter to early summer | Soil Type: | Rich, loamy, moist |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil pH: | 5.0-8.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-7 years or more | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | Width of mature spread | Attracts: | Birds, insects, mammals |

| Planting Depth: | 1/2 inch (seed), depth of root system (transplants) | Uses: | Border plantings, foundation plantings, groupings, native gardens, specimens, wildlife attraction, woodland gardens |

| Height: | 4 inches to 45 feet, depending on species | Order: | Cornales |

| Spread: | Indefinite (ground cover) to 40 feet, depending on species | Family: | Cornaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Cornus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, dogwood borer, club gall midge, mealybugs, sawfly, scale; dogwood anthracnose, fungal leaf spot, powdery mildew | Species: | Alba, alternifolia, canadensis, florida, kousa, mas, nuttallii, serica |

Doggone It, the Guide Is Already Over?!?

’Fraid so, amigo. That’s the way the cookie crumbles. Other hokey sayings.

But yes, hopefully you’ve gained a ton of dogwood know-how from this guide. From here, you’ll be able to adorn your landscape with a lovely Cornus or two. How’s that for awesome?

Still have questions? Brimming with your own wisdom to share? The comments section awaits you all.

And if you want to learn more about trees and shrubs for your landscape, read these guides next:

- How to Grow and Care for Arborvitae Trees

- How to Grow and Care for Chaste Trees

- How to Grow and Care for Yew Trees and Shrubs