How to Grow and Care for American Bittersweet Vines

American bittersweet is a wonderful, no-fuss addition to any wildlife or native plant garden. Learn how to grow this showy vine now at Gardener’s Path.

Celastrus scandens

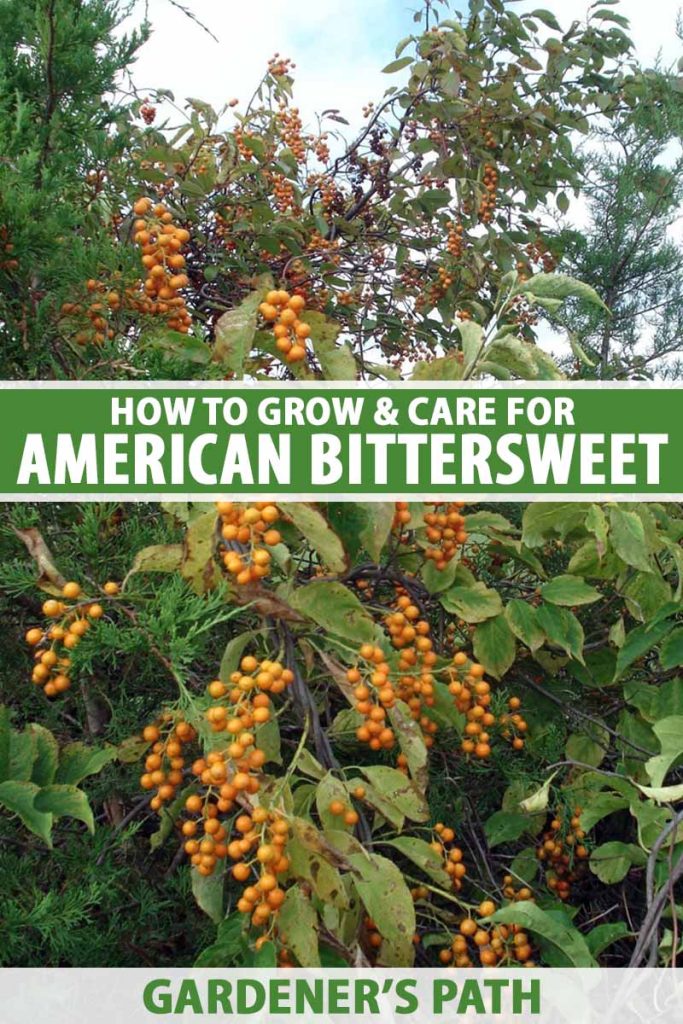

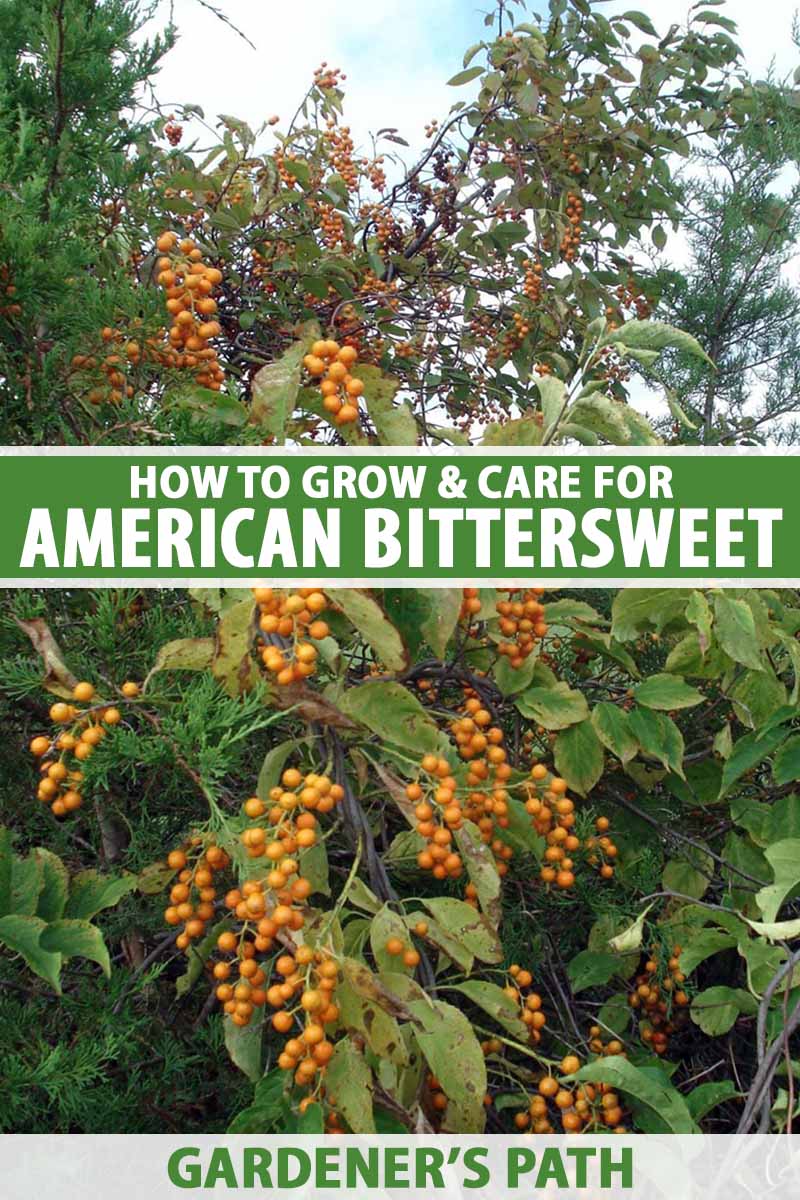

American bittersweet is the native congener, or close relative from the same genus, of a prolific invasive vine called Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus).

If you’ve driven down a highway or walked the edge of an old field almost anywhere in eastern North America you’ve probably seen the Asian invasive clambering over trees and carpeting shrubs.

In fact, you might have seen its beautiful, red and orange berries used in seasonal wreaths, too.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

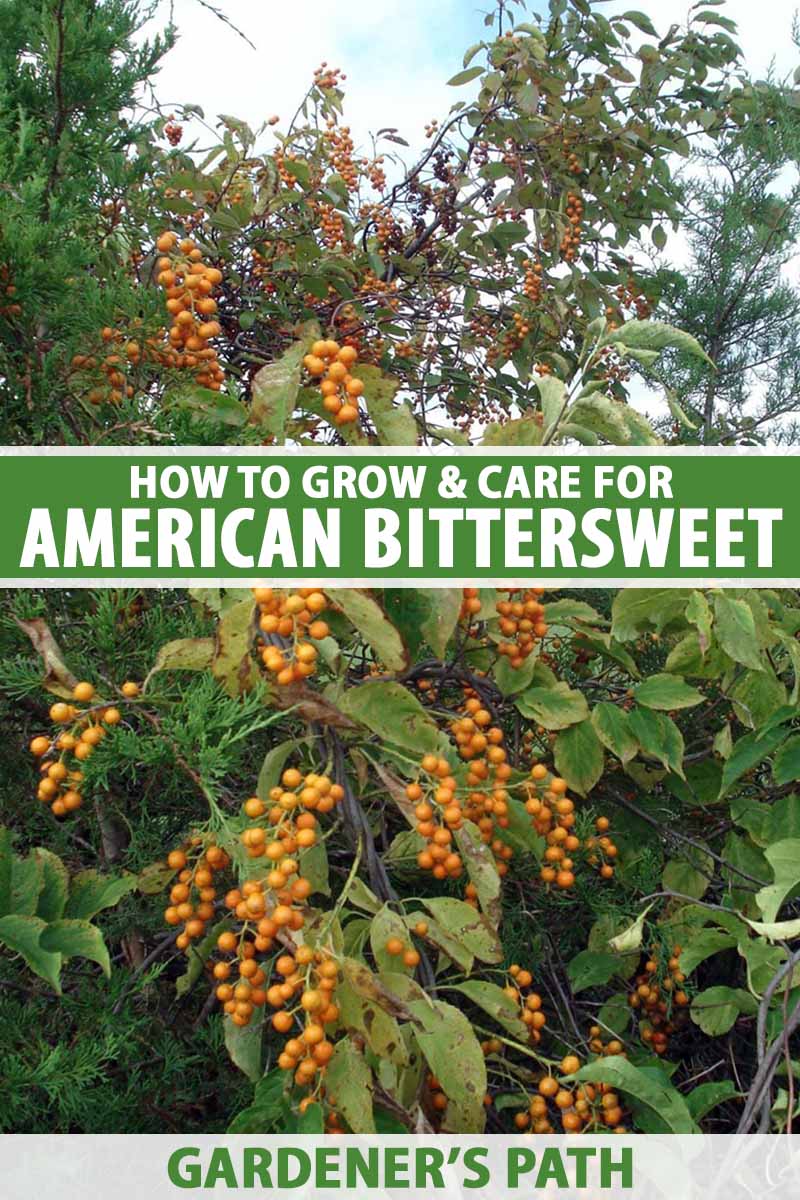

Fortunately, the little-known native bittersweet, C. scandens, is just as beautiful, but not as badly behaved. Forming large colonies in the wild, this woodland vine ranges across central and eastern North America.

In this time of climate change and habitat loss, it’s more important than ever to embrace native plants in the garden.

Turning your backyard into a sanctuary for pollinators, birds, small mammals, and more can do a lot to mitigate the ecological changes faced by wildlife these days.

Read on to learn more about how to identify and grow American bittersweet in your own backyard.

What You’ll Learn

- What Is American Bittersweet?

- Cultivation and History

- Propagation

- How to Grow

- Growing Tips

- Pruning and Maintenance

- Where to Buy

- Managing Pests and Disease

- Best Uses

- Quick Reference Growing Guide

What Is American Bittersweet?

A denizen of woodland edges and brightly lit glades, American bittersweet is a capable climber and lover of rich, preferably moist, soils.

Native to a wide swath of North America, this vine is extremely accommodating, tolerating lean soils, cold temperatures, and almost full shade.

Hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 8, C. scandens is more common in the warmer climes of the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast, however, the spread of its invasive cousin, C. orbicularis, has altered the native’s distribution.

What’s more, the two species hybridize, producing a plant that looks a little like both its parents.

The native species is pretty tricky to distinguish from the invasive. Both have rounded, oval shaped leaves that turn a lovely, pale yellow in the fall.

Both can grow quite quickly, and to great heights, in rich soils, and both boast clusters of orange berries with a firm, yellow casing, or carpel, covering them.

The berries are key to identification. While the invasive species produces what are known as “axial” clusters, nested in the lateral side shoots of the plant’s stem, the native makes “terminal” clusters, which are borne at the very end of the vine’s growing tip.

C. scandens has flowers that are cute and sweet, but fairly nondescript, pale green to white in coloration.

These of course are also positioned right at the tip of the vine’s terminal growing point.

Cultivation and History

Unfortunately, American bittersweet’s invasive relative is the bigger standout in horticultural history.

Introduced over 100 years ago, C. orbicularis was noted to have many of the same characteristics as its native relative, except for its ability to produce prolific amounts of the bright orange fruits which made it so sought after.

Once the new Asian bittersweet hit nurseries in the 1860s or thereabouts, American bittersweet went out of style.

Shortly thereafter, C. orbicularis jumped the garden fence and went rogue, beginning its invasive campaign in fields and woods across the country.

With the flourishing of the native plant movement, now is a great time to help return this piece of America’s ecological heritage back to the landscape.

Legend has it the native vine was utilized by native people to treat a variety of ailments including symptoms common to tuberculosis.

But before you leap for your mortar and pestle, remember to never use wild plants for medicine without the consultation of an expert.

American Bittersweet Propagation

American bittersweet is easy to establish in the garden as the plants tend to be hardy and vigorous.

The easiest method is to buy a mature plant at the nursery, but there are a few ways for the more adventurous at heart to get this plant growing at home.

From Cuttings

American bittersweet roots fairly easily from softwood cuttings taken from the plant’s growing tip. To do this successfully, you’ll need some sterilized pruners, a couple of four-inch pots, rooting hormone, and sterile potting soil.

Cuttings root best when taken from the soft, pliable new growth produced in late spring. A good four- to six-inch shoot will give you the best chance of success. Make sure you take your cutting right above a bud on the parent plant.

Pinch off the bottom set of leaves, dip the cut end in rooting hormone, and bury the bottom of the cutting in potting substrate so the nodes where the lower leaves were removed are level with the soil.

Cover with a plastic tent to ensure a humid environment and consistently moist soil.

You’ll still have to water your cuttings a little as they develop roots over the next four to six weeks. Using a spray bottle typically works well.

Place the pots in bright, indirect light and begin the vigil for new growth. As soon as you see a new green growing tip, take it as confirmation that roots have grown.

Rooted cuttings can be moved outside to be gradually hardened off before transplanting.

After transplanting, just be sure to baby them a little in their first year. They’ll need extra water and a lot of weed control until they grow stronger.

From Seed

Because the germination rate for American bittersweet can be patchy, growing this vine from seed is not a method I’d recommend unless you have a lot of experience.

Cultivating this species from seed also means you roll the dice when it comes to which sex you produce.

C. scandens seed has to be cold stratified, meaning it has to go through a prolonged cold period before it can germinate. If you buy seed online it likely will have been refrigerated to emulate the conditions of winter and prepare it for planting.

In spring, start American bittersweet seed in two- to four-inch pots indoors. Bury the seed just below the surface of the soil, no more than a quarter of an inch deep.

Keep the potting soil moist, but not soaking, until the seeds sprout. Make sure your pots receive a full six to eight hours of sunlight each day to aid and speed germination.

Once your little bittersweet seedlings have several pairs of leaves, plant them out in the garden as described below. Make sure to weed and water well for their first couple of years until they are established.

How to Grow American Bittersweet

American bittersweet needs little more than an appropriately sized hole in the ground to grow. Provided you are in Zones 3 to 8, it can do all the rest itself!

For the best production of berries, site your plant somewhere that receives at least six hours of sunlight a day.

The edge of a woodland or side of an arbor is perfect. Consider that this climber may reach up to 20 feet tall once mature, so give it room to spread.

If you’ve purchased a mature specimen, dig a hole a little wider and deeper than the plant’s root ball, cover its roots completely, and water well.

C. scandens prefers rich, sandy, well-draining moist soils such as those often found along rivers. A lightly acidic to neutral pH of around 6.0 to 7.0 is preferable.

If your soil is on the lean side, top dress with compost once a year in spring. This native vine’s water needs are relatively low so once your plants are established, there’s no need to water unless you’re experiencing a drought.

Male flowers are visited by a variety of small insects which will pollinate the female’s flowers and ensure fruit production come fall.

These plants are dioecious, so male and female flowers are found on separate plants. Make sure the female is within a few hundred feet of her mate to make this process easier and more successful.

To circumvent the often imperfect dalliance of cross-pollination and outbreeding, try ‘Autumn Revolution,’ a self-fertile variety.

Growing Tips

- Situate plants in full sun to dappled sunlight.

- If soil is lean, top dress with compost once a year.

- Water weekly and deeply during droughts or dry seasons.

Pruning and Maintenance

A true armchair gardener’s choice, there’s not much to do when it comes to American bittersweet maintenance.

If you happened to site your plants in dry, lean soil, make sure to top dress once a year with good organic compost and water deeply once a week.

Other than that, rein in your bittersweet’s tendrils and prune when necessary, then sit back and enjoy.

Although pruning American bittersweet is not necessary, you may have to remove some of the lateral shoots every once in a while to stop your vine from intruding on the space of other plants.

To create a bushier and more compact plant, trim up to a fifth of the plant in early spring, before leaf out occurs.

Where to Buy

C. scandens won’t be available at any run of the mill garden center. To find this level of horticultural novelty, you’ll have to sniff out a nursery that’s really native savvy.

Fortunately, you can buy plants online at Nature Hills Nursery.

American Bittersweet

Bear in mind most vines will be dioecious, meaning they’ll be either male or female. The nursery should list whether their plants are sexed or not.

If the vines are unsexed, it pays to buy a few to increase your chances of getting both pollinating males and fruit-producing females. Remember, you’ll need both sexes to get that colorful autumn crop of yellow and orange berries.

If you want to increase your number of females, follow the directions above on propagating cuttings, which will enable you to create clones of female plants.

‘Autumn Revolution’ and ‘Sweet Tangerine’ are two notable cultivars which are monoecious, meaning the male and female flowers occur on the same plant.

These plants are self-fertile and will produce berries on their own.

Managing Pests and Disease

Nearly as tenacious as its invasive counterpart, American bittersweet tends to be free of pest and disease problems.

The pests you’re most likely to encounter are typically nothing to worry about, unless your plant is stressed due to other reasons, like drought.

Two-Marked Treehopper

One such insect that falls into this category is the two-marked treehopper (Enchenopa binotata).

Native to North America, this springy little insect looks just like a thorn and loves to feed on the sap of woody plants like redbuds, ash trees, and American bittersweet.

Despite heavy feeding, this insect rarely causes enough damage to warrant intervention, unless plants are already under duress.

If you choose to control treehoppers, your plant will have to undergo some pretty heavy-duty chemical treatments that are best completed by a professional.

Two-marked treehoppers lay their eggs in slits in C. scandens bark and overwinter there, so they can be quite tricky to target.

If you’re having a problem with defoliation and stress due to a healthy population of hoppers, the best thing to do may be to add an extra top dressing of compost to your vine and treat it to extra weekly watering, too.

A little more TLC may provide the boost your plant needs to fend for itself.

Euonymus Scale

In some areas where the invasive euonymus scale (Unaspis euonymi) is present, C. scandens vines can be so badly affected that twig dieback or even defoliation occurs.

Euonymus scale is typically first identified by the small, white, waxy covering that houses the adult pests.

These little white cases appear all over the leaves and twigs in severe infestations. But it’s the crawlers, which first emerge in late spring and then again in late summer, which cause damage to the plant by feeding on sap.

If the infestation is minor, prune badly affected branches and destroy the cuttings.

If you’ve got a real mess on your hands, management of this pest will require carefully timed application of a horticultural oil such as neem oil, which is available for purchase at Arbico Organics.

Bonide Neem Oil

Be sure to follow the directions for preparing and applying this product – neem oil concentrate needs to be diluted before application, but scale requires the strongest possible dilution for effective control.

Be prepared to apply this product several times a year to target both the adult and juvenile stages of these insects. Typically this will mean application in winter to early spring, late spring, and late summer.

Remember to apply neem oil on cloudy, cool days or in the morning, so you don’t burn your plants’ foliage.

Best Uses of American Bittersweet

This native climber is a wonderful addition to the arbor, woodland fringe, or wildlife garden. Numerous species of birds will eat the berries including bobwhites, wild turkeys, and pheasants.

If you want to cultivate this species to use for seasonal decorating make sure to give it plenty of sunlight. It is a peerless choice for durable, dryable berries that hold their bright color over the years.

Note that the berries, if eaten, can cause a really bad tummy ache for both dogs and humans alike.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Vine | Flower/Foliage Color: | Greenish-white or yellowish/green |

| Native to: | Central and eastern North America | Fruit Color: | Yellow-orange capsule with red fruit inside |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 3-8 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Fall | Tolerance: | Drought, deer |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil Type: | Average |

| Time to Maturity: | 3-5 years | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Spacing: | 3 feet | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Top of root ball level with soil surface | Uses: | Wildlife garden, native plant garden, wreath making, seasonal decor |

| Height: | 15-20 feet | Order | Celastrales |

| Spread: | 3-6 feet | Family: | Celastraceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Celastrus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Euonymus scale, two-marked treehoppers | Species: | Scandens |

Nothing Bitter About It

Although this native’s common name alludes to its resemblance to another plant with the same name, C. scandens checks all the top gardening boxes:

A wise, eco-friendly choice? Check.

A low-maintenance, largely pest-free plant? Check.

A beautiful vining habit with four-season interest? Check!

Are you already growing this climber in your garden? If so, let us know how it’s doing! Or perhaps you’ve seen this native out in the wild?

Please feel free to share all your wins and woes with our readers in the comments section below. And if you need any help to get growing, let us know – we’ll be glad to assist.

Want to learn more about growing native species and other vines? Check out these suggestions:

- Native Vines for Your Landscape

- 19 of the Best Vines for Vibrant Summer Color

- 11 of the Best Non-Invasive Flowering Vines to Grow in the North