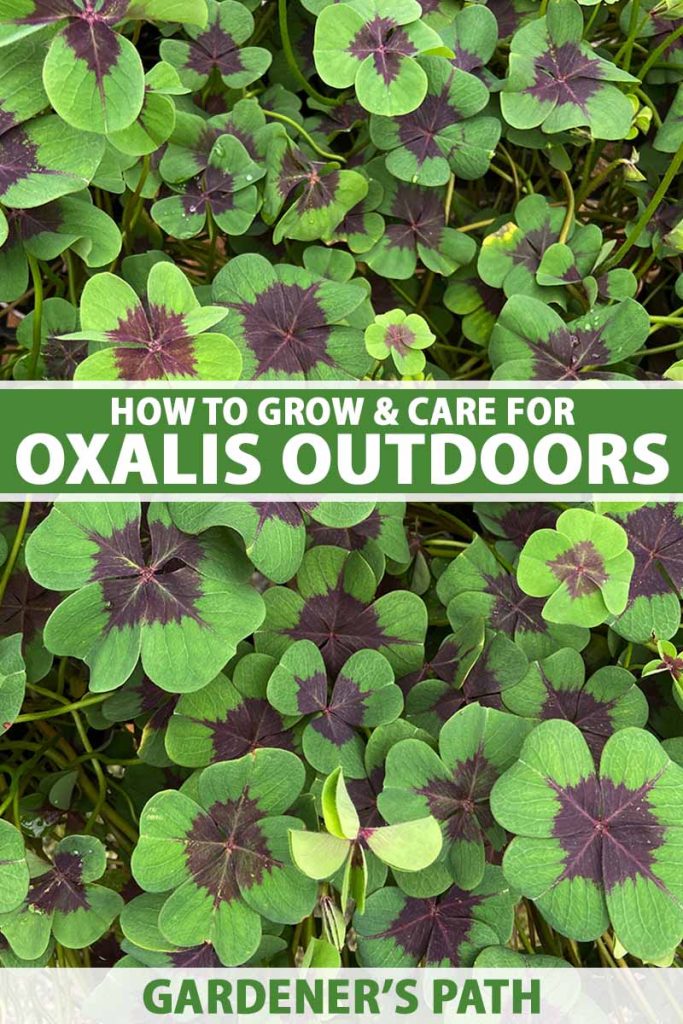

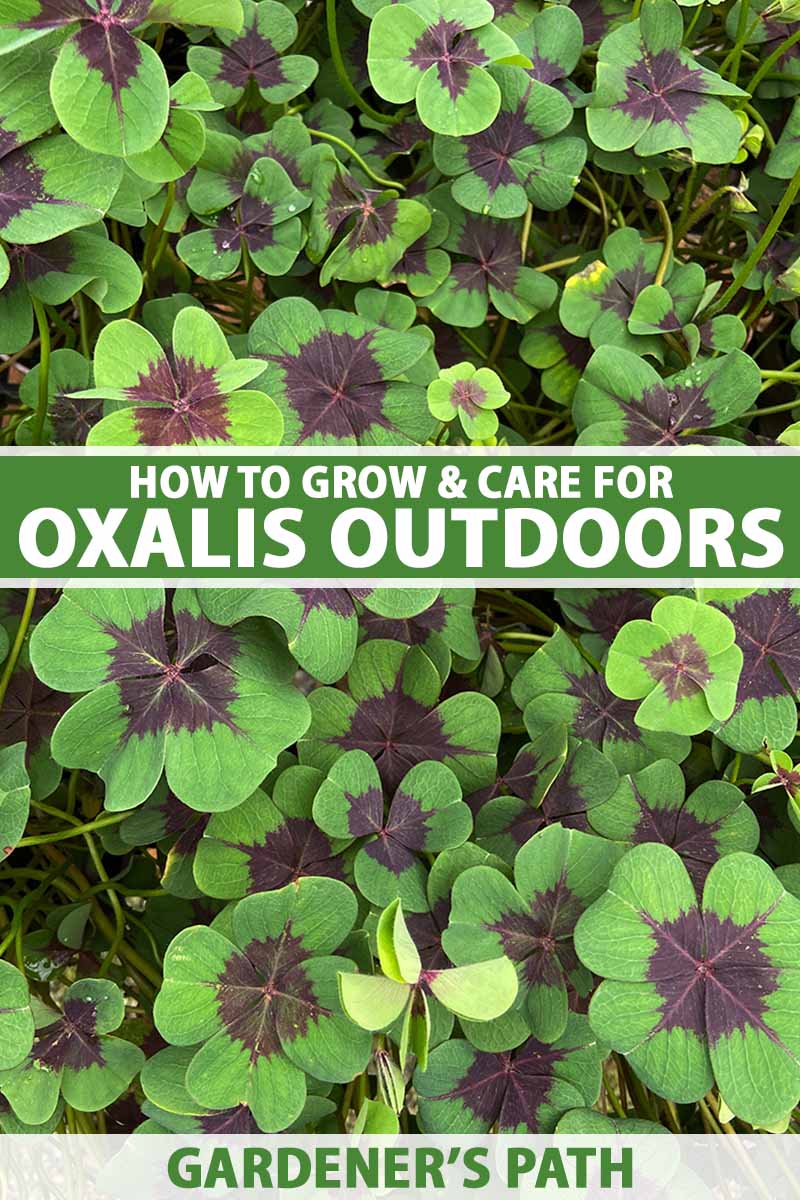

How to Grow and Care for Oxalis (Wood Sorrel)

Multipurpose oxalis plants can be grown effortlessly. Learn about the many species, their uses, and how to make them thrive outdoors now on Gardener’s Path.

Oxalis spp.

If you’ve ever wandered around the garden section of your local grocery or home supply store around St. Patrick’s Day, then you’ve probably seen cute little containers filled with shamrocks.

They’re a whimsical piece of holiday decor for your kitchen table. But as much as I love these adorable plants, they only begin to scratch the surface of what the Oxalis genus is capable of.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Humble little oxalis plants come in multiple different leaf sizes, colors, and shapes, along with flowers that can be adorably petite or big and bright.

They’re edible, can be used to replace lawns, and require little care once you plant them.

And if you choose a native species, you’re going to improve the overall health of your garden by inviting important pollinators.

And if that doesn’t give you enough reasons to fall for oxalis already, it’s also basically impervious to pests and diseases.

Even if a pest or pathogen is foolhardy enough to bother a patch of wood sorrel, this plant can easily shrug it off.

Isn’t it nice to be able to focus on your fussier plants, knowing there’s an ol’ reliable out there humbly chugging along?

There’s a lot to know about this group of plants that often seem to fly under the radar. We’re going to go over the following so you can become an Oxalis oracle:

What You’ll Learn

- Cultivation and History

- Propagation

- How to Grow

- Growing Tips

- Maintenance

- Species and Varieties to Select

- Managing Pests and Disease

- Best Uses

- Quick Reference Growing Guide

A beautiful garden features various focal plants.

You know the ones – the eye-catching roses, hydrangeas, and clematis. But it also needs more subtle background fillers, like grasses, creeping juniper, and, you guessed it: Oxalis.

Obviously, I’m already sold on these plants.

I’ve loved them ever since I first started urban foraging decades ago because they’re instantly recognizable and they’re everywhere. And I’m going to convert you, too. Just try to resist!

Cultivation and History

There are hundreds of species within the Oxalis genus, as well as six subgenera.

Oxalis grows wild on every continent except Antarctica. They’re one of those types of plants that fill in unnoticed, quietly growing nearly everywhere in the world.

Most varieties produce leaves divided into three leaflets, and they’re often confused with clover. But Oxalis species are truly diverse, and highly adaptable.

Depending on the species, they can have taproots, rhizomes, or tubers (actually corms) growing underground, and their leaves can vary widely from single oval-shaped foliage to large leaves composed of five heart-shaped leaflets.

All have a single flower per stalk and one set of leaves per stem.

So, are they shamrocks? Technically, there’s no such plant.

Shamrock is a common term for a small tri-leafed green plant, and it may be used to refer to various Trifolium, Medicago, and Oxalis species.

Oxalis plants are often called wood sorrels, but don’t confuse them with sorrel or broad-leaf sorrel (Rumex acetosa).

These are another type of edible “weedy” wonder that you can forage across the globe or cultivate at home, but they aren’t at all related.

All Oxalis species are edible, but they vary in their palatability. You shouldn’t eat too much all at once, though, regardless of the species. All species contain oxalic acid, which binds to calcium, making it unavailable to your body.

People with gout, kidney stones, arthritis, and/or hyperacidity should probably avoid eating oxalis altogether. The rest of us can enjoy it both ornamentally and as a snack.

They’re full of good nutrients like vitamins A and C, as well as iron.

If you have any cross-Atlantic sailing journeys scheduled, bring some along to recreate the historic experience of ocean travel. The leaves were once a common treatment for scurvy.

These perennials can live for a long time, and they also spread and create new plants quite readily. Oxalis will self-seed and spread underground.

Representatives of this genus haven’t been cultivated extensively.

O. tuberosa is the only species commonly cultivated for food and there are a few species grown and sold for their ornamental leaves or flowers.

The two most common are O. versicolor, which has showy blossoms, and O. triangularis, which has large purple leaves.

We’ll talk about those and more in a bit. But first, let’s discuss how to propagate Oxalis to get started in your garden.

Propagation

Whatever species you decide to grow, I highly recommend choosing a native one.

Unless you’re growing Oxalis for the edible tubers or for flowers specifically, there are so many options to choose from, and there’s no reason not to pick a local species.

Not only is it better for you, in terms of how little care and time you’ll need to dedicate to cultivation since these plants will do best within their native range, it’s also better for local fauna.

If you do want to grow them as veggies or for their flowers, cultivation may be a bit more time-consuming, but you can do that too.

Most are fairly obedient and stay where you put them, though some can potentially become a nuisance. A few species have recently started to invade wild areas, like O. pes-caprae in California.

Check local environmental regulations to see if there are any species of concern in your area before planting a non-native variety.

From Seed

To propagate Oxalis from seed, stroll by any remotely disturbed patch of soil in the spring and casually drop the seeds. There you go! You did it!

I’m joking, of course, but this plant is one of those fascinating species that shoots its seeds out of the pods.

They land nearby and the cycle starts all over again, and this method of reproduction means it’s an easy plant for us to propagate from seed without too much fuss.

The secret is to be sure you’re sowing or sourcing fresh seeds. Older seeds won’t germinate.

Gently rake the surface of the soil and sprinkle the seeds on top, aiming to keep them about an inch apart. Lightly press the seeds into the surface or barely cover with an eighth of an inch of soil.

Sprinkle water onto the soil, and that’s pretty much it. Your biggest challenge will be keeping birds away, as you would do with any type of seed that you sow on the surface of the soil. Tent some chicken wire over the soil if birds are a problem.

From Corms or Tubers

For some species it’s best to propagate the bulbs (actually corms, rather than true bulbs) or tubers. You’ll often find four-leaf and purple shamrock oxalis corms for sale rather than seeds.

To plant these in the garden, wait for spring and dig a small hole for each corm so that it sits about an inch or so deep, leaving about six inches of space between each one.

Lay the corms in the holes. It doesn’t matter if you lay it sideways, upright, or upside down, it will still grow.

Cover the corms with soil and water them in.

By Division

Once a mature oxalis has started to grow and spread, you can divide it.

Stick a shovel firmly into the center of the plant to split it in half and continue halfway around the outside perimeter to dig it out of the ground. Gently lever the loosened half up and out of the soil.

Plant the divided section in a new hole to the same depth, and fill in the hole where you removed the daughter plant with potting soil.

Transplanting Nursery Starts and Seedlings

You can find some species at nurseries during the spring, and of course, you can always transplant those cute shamrocks you find in stores around St. Patrick’s Day – just make sure what you have is actually an Oxalis species.

Specialty nurseries will likely carry at least one native species local to your area if you want to go that route.

You can transplant seedlings at any time of year, but it’s best to do so in the spring or fall. They’ll do best when the weather is cooler and rain is more likely.

Dig a hole about twice as wide and the same depth as the container the plant came in. Remove the seedling from the pot and lower it into the hole.

Fill in around the seedling with potting soil or well-rotted compost mixed with your native soil. The loose, rich soil surrounding the Oxalis plant will give it a good head start.

Spacing varies depending on the species, but on average these need about nine inches on all sides.

How to Grow

Wood sorrel can tolerate pretty crappy soil, but it needs good drainage. If the roots are stuck in soil that’s constantly wet, the plant will die.

Don’t worry too much about sandy or clay soil. Just work in some well-rotted compost or manure and it will be fine.

Or don’t! Really, Oxalis can survive in all but the most extreme soil conditions, but they won’t be as compact or robust if grown in poor soil.

Another exception is if you’re growing this Oxalis to harvest the tubers. Then you want to be sure to plant in rich, loose soil so the root system can expand.

Oxalis can handle a range of soil pH levels but it’s best to aim for something mildly alkaline, ranging from 7.2 to 7.8.

Most species will survive in full sun but they do best in partial shade, especially if that shade is cast on the plants during the hottest part of the afternoon.

These will also keep on trucking in full shade but they won’t look their best, and certainly won’t be as colorful or dense as they could be with more sun.

When it comes to water, you’re going to have to be extremely careful and remain constantly vigilant…

Haha! Just kidding! Once again, Oxalis makes things easy on you. And if you go with a native species, it will be even easier.

Native plants have adapted to the average moisture found in the environment of your local area and you’ll probably only have to water occasionally, if ever. I watered my native plants a couple times this summer because we had an unusually dry one.

If you choose a non-native type, familiarize yourself with its requirements. Most need to be watered when the soil is nearly but not completely dry.

All can tolerate some occasional drought, but they’ll wilt and struggle until they receive the water they need, at which point they’ll perk back up.

Some are more drought-tolerant than others, but again, none of these do well in soggy soil.

Feed your plants once a year with a mild, all-purpose fertilizer. Or, again, don’t.

Any plant that takes over when other plants falter, as oxalis does, is a plant that doesn’t need rich soil. I just toss some well-rotted manure around my plants in the spring and call it a day.

Down to Earth All Purpose Fertilizer

If you want to go the less lackadaisical route, grab a one-, five-, or 15-pound compostable box of Down to Earth’s All Purpose fertilizer at Arbico Organics and apply it according to the manufacturer’s directions in the springtime.

Growing Tips

- Plant in part sun or part shade.

- Fertilize or side dress with manure once a year.

- Don’t let the soil dry out completely.

Maintenance

If your plant starts to look a bit leggy or unkempt, go ahead and prune it back. Go way back, if you want!

You could cut the plant back to the ground in the fall and it will pop back up in the spring. Many species die back like this naturally, anyway.

If you use this plant as a lawn replacement, go ahead and mow it with your mower set on the highest setting a couple of times a year to keep it compact and tidy-looking.

This isn’t necessary, but if you miss the uniform look of grass, it’s a good way to recreate a similar appearance.

Species and Varieties to Select

There are dozens of species of oxalis. To make things easier on yourself, go with a native option or at least one that grows in a climate similar to yours.

All species can be grown as annuals if they aren’t suited to your particular growing zone.

Here are a few recommended varieties for your consideration:

Deppei

Four-leaf sorrel (O. deppei aka O. tetraphylla) is a species that stands out with its four-leaflet leaves.

‘Iron Cross’ has distinctive green foliage with a dark red-purple-brown splotch in the center.

It’s an excellent option if you’re looking for a St. Patrick’s Day shamrock, thanks to its eye-catching pattern and distinctive leaflets.

Grow it as a perennial outdoors in Zones 7 to 10, or as an annual. Four-leaf sorrel grows taller than many other species, reaching heights of over 12 inches.

‘Iron Cross’

Lucky for you, you can pick up 20 corms at Amazon from the Easy to Grow store.

Just watch out, the rest of this species can be a little bit weedy, so you might need to put in some extra effort to keep them in check.

Oregana

Redwood sorrel (O. oregana) is the very best Oxalis there is in the whole wide world, hands down, and I’m not at all biased just because it’s native to my neck of the woods.

Okay, I’m entirely biased. But I think it’s awfully cute, even if it isn’t as showy or tasty as some of the other species out there.

This plant has distinctly heart-shaped trifoliate leaves and produces a single rose-colored flower on each stalk. The blooms hang out all summer, making for an attractive show.

The reason this species is a standout, beyond the bright flowers, is that it forms an extremely dense carpet only about six inches tall.

It’s suitable for replacing lawns, particularly in shady areas. Plus, it won’t go weedy in the right environment and jump out of your yard to spread elsewhere like some of the other species tend to.

Grow O. oregana as a self-seeding perennial in Zones 6 to 9.

Triangularis

O. triangularis is arguably the most common ornamental species in the US, for cultivation either indoors or out.

You’ll see this six- to 12-inch-tall plant adorning tables, bars, and shelves in Irish restaurants and stores around St. Patrick’s Day.

The leaves can range from medium green to dark purple. They have white or pink flowers, and this plant likes it warm. It’s hardy in Zones 8 to 12.

Purple Shamrock

If you’re interested in adding this perennial fave to your garden, grab 20 corms from the Easy to Grow store at Amazon.

Versicolor

Candy cane sorrel is native to South Africa and, unlike most other species, it’s grown for its striking flowers.

Each blossom has five petals that are white on the inside and white with red borders on the outside.

This species grows in Zones 7 to 9 and blossoms from September through early winter.

Managing Pests and Disease

One of the reasons that people use Oxalis as a replacement for traditional turf, in addition to the whole no-mowing thing, is that it’s one tough cookie.

Though there are pests and pathogens that may attack these plants, the chances of any of them becoming enough of a problem that gardeners must resort to treatment are slim to none.

Here are a few to keep an eye out for, that you may encounter:

Insects

Aphids are the only common pest that you’re likely to see on wood sorrel, but they shouldn’t pose a problem.

They can become a concern in large numbers on indoor plants, but don’t worry yourself too much outdoors.

Learn more about cultivating shamrock plants and other varieties of oxalis indoors in our guide.

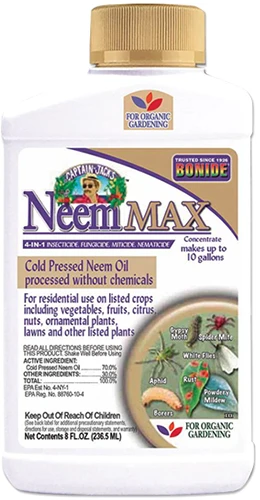

If you do see aphids and you have just one or two plants, prune off any heavily infested branches and spray the plants with neem oil.

I keep neem oil around because it’s such a handy solution to so many problems.

Bonide Captain Jack’s Neem Max

If you don’t have any in your gardening toolkit already, pick up an eight- or 16-ounce container from Arbico Organics.

If you have a big patch of plants that are infested, honestly, don’t worry about it.

Spray the plants with a strong blast of water from the hose once a week for a few weeks and the aphids will move on.

Disease

It’s rare to see disease with these plants.

It’s just not something that happens often, particularly when growing native species in suitable environments. But if you do spot signs of infection, don’t stress.

You usually won’t have to do anything, though disease is almost always an indication that the environmental conditions aren’t ideal.

Improve the growing area as needed for your plants and they’ll take care of themselves.

Be on the lookout for:

Leaf Spot

Leaf spot is the most common issue when growing Oxalis, and it’s caused by Phyllosticta guttulatae, Ramularia oxalidis, and Septoria oxalidis fungi.

When this disease appears, it’s almost always a problem with plants that are suffering from a lack of light in conditions that are too shady, and that are watered by sprinkling the foliage rather than irrigating at the soil level.

If you provide your plants with the right amount of sun, water only at the soil level, and don’t overwater, it’s unlikely that you’ll encounter this issue.

If you do run into leaf spot, relocate your plants or do some pruning to increase airflow and light exposure. Always be sure to water at the soil level.

You don’t need to treat your plants in any way if you take steps to improve the environmental conditions, but be sure to remove and dispose of any heavily infected leaves.

Rust

All species of oxalis are susceptible to rust, which is caused by the fungus Puccinia oxalidis.

The leaves will be covered in yellow-orange fuzzy spots on the undersides, and the upper sides will look curled and discolored.

The fungus favors wet conditions, which is why watering at ground level is best.

You can treat a rust infection with copper fungicide, but if you reduce the amount of water allowed to accumulate on the leaves by using drip irrigation or a directed watering nozzle and irrigating in the morning, this disease should resolve on its own.

If a plant really seems to be struggling, spray it with a liquid copper fungicide once every other week for six weeks.

Best Uses

There are multiple ways to use Oxalis – and I recommend you take advantage of using the plants you’re growing yourself in multiple ways!

A common veggie in many parts of the world, even if you don’t grow the tubers, you can eat the leaves of any species. Some are more tart than others, but they all have something to offer.

The tubers should be ready for harvest in the fall. You’ll know it’s time when the foliage starts to die back.

Dig down beneath the root zone and gently lift the plant up with a garden fork. Shake any loose soil off the tubers, and wait to wash them until you are ready to use them in the kitchen.

The tubers are fantastic roasted in oil or butter. Toss in some garlic, spinach, kale, lentils, and carrots, and you have a meal!

Use the leaves in salads, soups, sandwiches, cocktails, and pasta dishes.

Just remember not to eat too much at a time or repeatedly for an extended period because oxalic acid intake can impact calcium absorption.

If you were to eat an ounce of the leaves in one sitting, you run the risk of making yourself feel extremely sick.

You can also grow oxalis as a low-maintenance ornamental, in beds and borders, or in containers.

Finally, use it as a lawn replacement. Though oxalis isn’t tough enough to stand up to a soccer tournament, it can handle regular foot traffic, and the flowers are prettier than anything a grass lawn can give us.

Plus, there’s always a benefit to local fauna when you ditch the monoculture and include more variety in your landscape. Pick a native species for even greater benefit.

A lot of people spend time and money trying to push this plant out of their lawn. But I say, embrace it! I’ve never seen a grassy front yard blossom all summer long.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, pink, purple/green purple |

| Native to: | All continents except Antarctica | Tolerance: | Some shade, some drought |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-12, depending on species | Maintenance: | Low |

| Season: | Spring, summer, fall | Soil Type: | Moderately sandy, loamy, moderately clayey |

| Exposure: | Partial Shade | Soil pH: | 7.2-7.8 |

| Time to Maturity: | 3 months from seed (foliage), about 5 months from seed (tubers), depending on species | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 1 inch (seeds), 9 inches (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Ferns, hostas, vinca vine, wood violets |

| Planting Depth: | Surface (seeds), 1 inch (corms), same depth as container (transplants) | Uses: | Ornamental, vegetable, lawn replacement |

| Height: | Up to 2 feet | Order: | Oxalidales |

| Spread: | Indefinite | Family: | Oxalidaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | Genus: | Oxalis |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Acetosella, corniculata, corymbosa, deppei, oregana, purpurea, regnellii, triangularis, tuberosa, versicolor |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, caterpillars, crickets, fungus gnats, slugs, snails | Varieties: | Atropurpurea, corymbosa |

Oxalis Is an Unsung Wonder

I think more and more gardeners are realizing today that there’s a lot of value in some of the more humble plants like wood sorrel.

Maybe enough of us are just sick of babying our lawns with heaps of fertilizer and weekly mowings, or fussing over ornamentals that seem to have the singular goal of dying as soon as possible.

Some of us are also crazy about lesser-known edibles, especially ones we can forage out of our own backyard.

I hope you feel like an Oxalis oracle (trademark pending) after reading this guide. I can’t wait to hear about how you plan to use your marvelous plants.

Which species are you going with? What will you do with it? Let us know in the comment section below. Recipes are particularly welcome!

Feel like you haven’t gotten enough of these multipurpose wonders? Here are a few other articles about herbs to check out next:

- 39 Common Weeds That You Can Eat or Use for Medicine

- Tasty Turf: Tips for Using Culinary Herbs as Ground Cover

- How to Plant and Grow Purslane